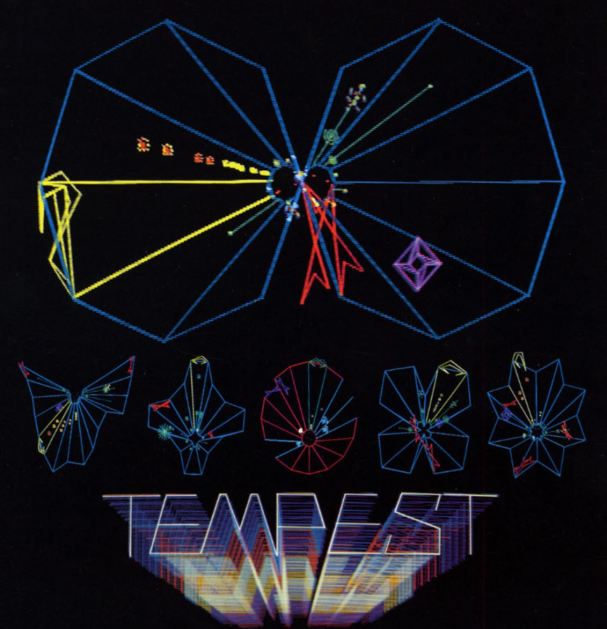

It’s a brave man who tries to criticize Atari’s seminal groundbreaking game Tempest. More than any other classic arcade game, Tempest hit the arcade scene like a juggernaut. Nothing like it had been seen before, and arguably, nothing has come close since.

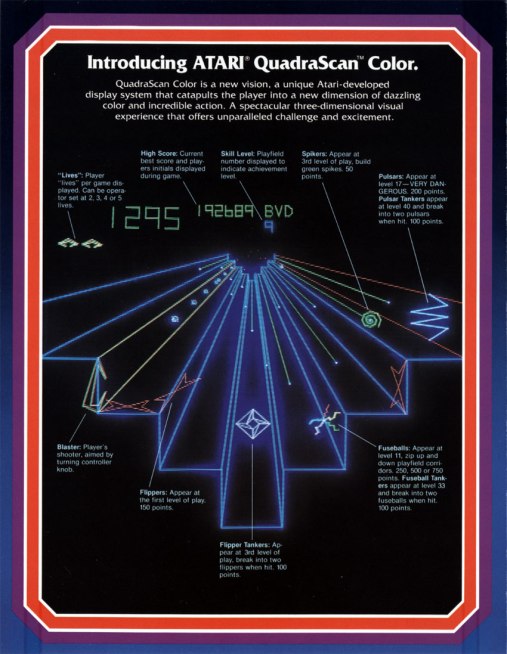

As Atari’s first full colour vector game, Tempest not only broke new technical ground, reinforcing Atari’s position at the top of the arcade development scene, but also threw something completely new at the playing public.

This week, I wanted to take a more detailed look at how the game was made. Its creator, Dave Theurer had just finished up Missile Command, having previously worked on Atari’s Four Player Soccer game. Now highly respected internally at the company, he had very quickly been catapulted to Superstar Programmer status.

So much so that Atari’s arcade division had an unwritten rule known as Theurer’s Law, which stated that “No designer gets his/her first game published”. It was named after Theurer (rather perversely), as he was the only designer up to that point to have his first game released – something normally unheard of, as most programmers would stumble at their first attempt. That game was none other than the illustrious Missile Command, a huge hit for Atari, eventually selling over 14,000 upright units.

Probably more from his own sense of drive and desire to succeed, Dave found himself under pressure to produce another hit game. After the success of Missile Command, and its rise to cult status amongst the playing public and internally at Atari, what was going to be next? Deciding on what to work on would be largely his own decision, and at Atari, there were two ways of going about choosing an idea for a game:

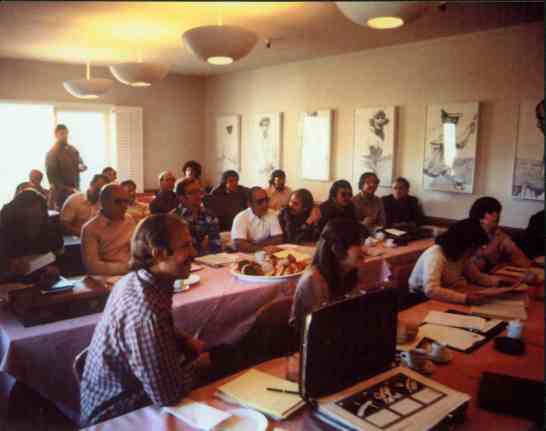

Programmers could either come up with their own scope for a game, and literally pitch it to the management of Atari’s Coin Operated Division for approval; or pick an idea from an already-approved catalogue of ideas. This catalogue was an actual physical book, full of generic ideas that came out of regular brainstorming sessions, where the whole coin-op team would camp down someplace away from the office, and discuss new proposals for upcoming games that they thought might work.

Dave recalls a place an hour away from Atari’s Sunnyvale offices in Santa Cruz County called Pajero Dunes as being a particularly favourite location for these away-day sessions.

Dave picked an idea from the catalogue simply titled “first person space invaders”. Reference to this concept was first mooted at a brainstorming session that took place on 6th February 1980. Dave wasn’t at that meeting, as he was still putting in long hours getting the finishing touches to Missile Command in place. It was one of many ideas discussed, as this internal Atari memo confirms.

After a couple of weeks intensive programming, he had built a demo which was indeed a first person shooter. After presenting it to management, the resounding feedback was that the game wasn’t much fun. Dave recounts:

The initial gameplay was to be simply a ‘First Person Space Invaders’. I got it up and running, but it wasn’t much fun. Too much like Space Invaders (surprise surprise). So after the review they said do you want to kill it? Or have you got any other ideas? I said ‘I’ve got this nightmare I have, where monsters are coming out of a hole in the ground and I’ve got to kill them before they get to the surface and kill me. Let me just take the first person space invader game and wrap them onto the surface of a hole (tube) in the ground’.

Trusting his judgement, management gave Theurer the green light he was looking for. But there were further problems with his next iteration, once he’d tweaked the original brief:

I first tried rotating the tube instead of the flipper, but that made everybody want to puke.

Clearly not an ideal situation for a video game intended for public release! Having the whole tube rotating was also a lot of work to program, and put a lot of stress on the code. Thinking laterally, Theurer came up with a simple solution: create the tube shapes as a static playfield, and have the player’s yellow “flipper” character move around the upper edge of the vector tube structure. The mechanic turned out to be fun and the feeling of induced nausea was no longer an issue.

With that problem solved, he knuckled down to building the guts of the game. Working at Atari coin-op was both fun and incredibly pressurised. Dress-code was as informal as it could possibly be (shorts and t-shirts were usually the order of the day), and there were opportunities to relax during regular Friday night parties and get-togethers.

But the hedonistic lifestyle of an early 80s Atari programmer had many downsides. Huge amounts of overtime were not unusual to meet to continuing demand from management who had an eye on release schedules and sales targets. Dave often referenced the intense nature of the work back then, often citing sleeping at the office and working through the night to get his game to where he felt it needed to be. Prior to having a game ready for a field test, Theurer describes times where he would go three or four days without sleep. A normal 24 hour day would simply go out the window. The impact on personal lives, Dave’s included, was sometimes catastrophic.

The culture within Atari Coin-Op was one of intense competition – competition for your game to be “hot” and ready to roll within the time pressures imposed by the company.

The hardware he was trying to use, and the constraints of the creative process did little to ease matters. Theurer had to work within what seems now a very antiquated and disjointed programming work stream.

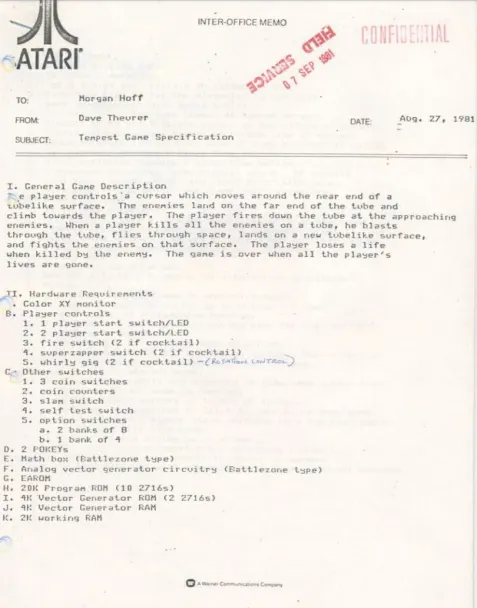

As the main programmer, Theurer was ultimately responsible for the design of the game. In the case of Tempest, that meant everything from the graphics, sounds, and the way the game actually played – this was a far cry from the hundreds of people who will work on a single video game today. Alongside him would be a hardware specialist who would design a unique new piece of hardware for the game (a vector generator and mathbox in the case of Tempest), and under him would be a technician, whose primary job would be to keep the hardware working as it was being developed. Attached to the team would be a project manager who would take care of general internal red tape and co-ordinate cabinet designs, manuals, artwork and field tests with the other departments.

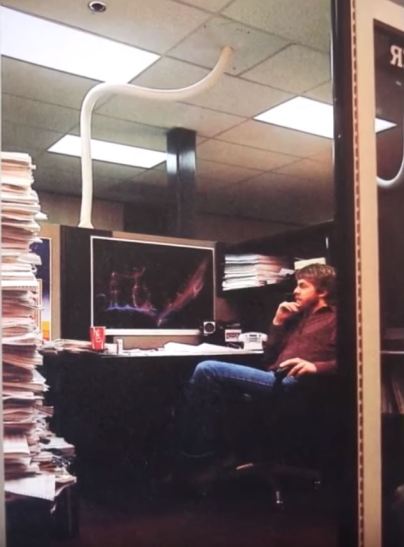

So armed with nothing more than his mind’s-eye vision of a game, Theurer would lock himself away in his office and program for hours on end:

The programmer had to do everything: Write the whole operating system from scratch, design all the graphics, write the tools to do the graphics, create sound tools, and do the sound design – everything from scratch for every game….I’d write the code on programming sheets and turn it in to the typists who’d type them in to a DEC computer, then give us a tape with the resulting compiled/linked program. We’d then take that to a blue box [which used the FORTH programming language] for debugging. We’d mark changes to the code on a listing, give it back to the typists who’d edit our files and give us a new tape. Repeat ad infinitum.

I guess the technicalities of what he describes are not important here, but even to a layman, that process is hardly what you would call slick. The debugging process was done at the cabinet itself, leaving desks clear for actual writing of code – with pencil and paper. But its worth remembering that despite itself, this way of working created some of the most iconic arcade games ever released.

The hardware in particular caused many headaches along the way. Tempest was using brand new components, especially in the new Wells Gardner Quadra-Scan 6100 vector monitor – a world’s first that was capable of producing vector graphics that were multi-coloured. Theurer recalls some of the issues involved in working with what was essentially prototype hardware:

I remember one time in the lab, the monitor stopped working and we looked up under the [chassis] circuit board and it had got so hot, that four or five of the components had de-soldered themselves and fallen out onto the table.

Aware that he was programming routines never seen before in video games, Theurer had to be conscious of the demands he was placing on the 6100 hardware. His tech guy kept up as best he could, but as any arcade operator or collector will tell you, the reliability of Tempest’s hardware leaves a lot to be desired.

Tempest was the first game to use the color vector generator. I’m sure there were things they discovered in production after doing Tempest and a few other games that enabled them to protect the monitors and make them last longer. Maybe the monitor was vulnerable to being destroyed by the software, and I did things to it that the other programs didn’t, like when you blast down the tube, and vectors get drawn all the way out past the edge. Perhaps that fried it!

Hardware challenges aside, Theurer knew his game was going to be “hot” before it was even field-tested. Hoards of staff would converge on his lab to play the game. The feedback was irrelevant – everyone wanted to try out the new vector shooter that was coming to life. This told him everything he needed to know, and he often had to shepherd people out the door just to get to back to work on Tempest.

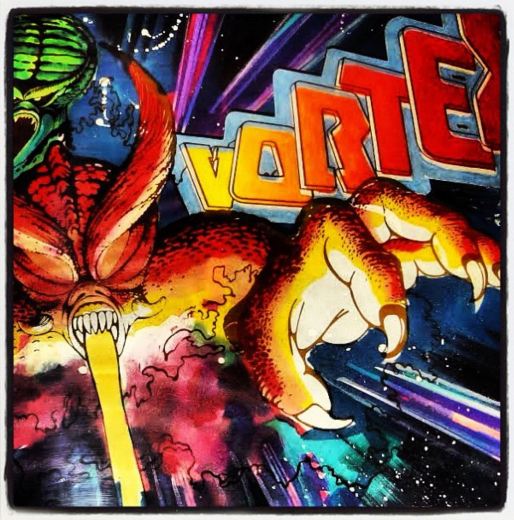

A footnote of sorts here; we know the game as Tempest, but it was initially code-named Aliens Vector, and then went by a different name for some time – Vortex. Internal documents from Atari make reference to Vortex as late as June 1981 – just four months before its final release date. The Vortex ROM has since turned up and been released as an add-on kit to the main Tempest code – video here. Although largely identical to the final game, it’s still interesting to watch even just for the different attact mode.

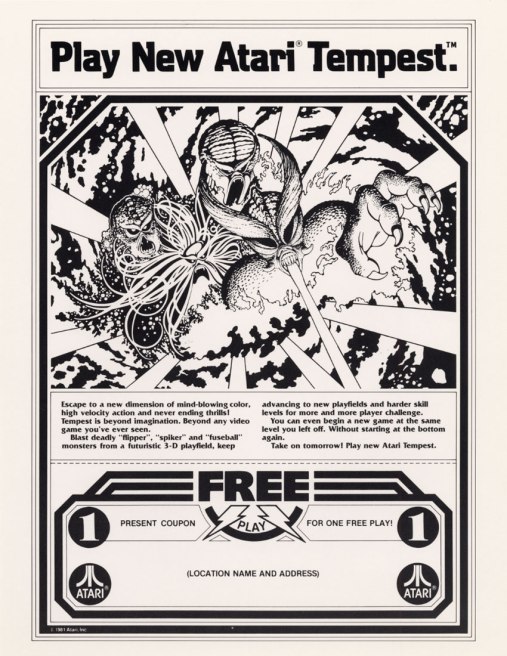

With the game almost ready by fall 1981, the creative artists at Atari designed the concept artwork that we now know and love. The monster characters add to the feel of the game and give the player another hook upon which to latch on to – adding to the futuristic looking bespoke angular upright cabinet, the result was something special:

Although known for his ability to overcome complex software problems, and create cutting edge video games, it’s important to remember that Theurer still kept his eyes on the prize; which was Atari’s mantra of creating great games that were fun to play:

It was just so exciting working on these new games. All my life I loved explosions. When I went to college I was a chemistry major because I wanted to do something where I could make explosions. When I was a kid I had a chemistry set and I’d blow stuff up all the time. Eventually, you learn that you can’t really do that in real life, so the next best thing is to do it on the screen, so here I was blowing stuff up on the screen. Simulating real life is fun too. It’s almost like you can create your own universe. Well, you are creating your own universe. That’s rewarding, to see something come alive.

I want to design [games] for a guy who’s totally frazzled by his job and needs a way to temporarily escape. There’s a certain class of games . . . where you just get into a trance when you’re playing them. As long as you’re in this trance you’ll do fine.

Demand for the game was unprecedented, and although it suffered from hardware issues (and a software bug inadvertently created by Theurer, where a 12% chance of 40 credits being obtained by a player scoring 170,000 points in one game can occur), Tempest turned out to be a bigger success than Missile Command. Over 25,000 uprights, 2,000 cabarets and 1,600 cocktail machines were produced.

Today, Tempest remains a stunning achievement. Collectors are able to add reliability to the monitor with newly designed hardware housing updated parts. The game is a jolt to the senses, and the glow of the vectors produced are hypnotic after extended play.

And the original arcade version still has active players. As recently as last year, people are still breaking world records on Tempest. Some great footage here showing the long standing WR being taken down:

That it is able to hold one’s attention even today, lays testament to Theurer’s uncanny ability to take hardware that no one had ever used before, and create a game with depth and a unique beauty that is actually fun to play.

Thanks for reading this week. If you like what you see, I’d appreciate it if you could share this article using the social media buttons below.

See you next time.

Tony

More reading/viewing:

My restoration of an Atari Tempest cabaret cabinet

Atari Tempest Time Lapse Photography

I knew parts of this history, but really enjoyed the read. Great job.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Having been in the arcade business since the early seventies I’ve seen a lot of video games Tempest was always my favorite.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Love this retrospective, and all the background on the making of the game.

I loved Tempest 2000, the Jeff Minter remake on the Atari Jaguar, and Tempest is still one of the all-time greatest arcade games!

LikeLiked by 1 person

great post thanx a lot for the many infos included !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another great write up Tony. Lots of detailed info here providing an insight into the world of Atari and it’s titles.

Tempest is an outstanding cabinet which looks every bit as good as it plays.

Definitely one to own in the future.

LikeLike

Great job on this article! Tempest is my all-time favorite game. You might enjoy the video I made showing off the 40-credit and level select cheats: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iSMIRKSztPQ

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mark that’s really cool – thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Here is another video hot off the presses! 1,000,000+ score on default arcade settings. My all-time high score! https://youtu.be/tllLkJY_wrI

LikeLike