It struck me that we’ve not yet featured any Laser Disc arcade games here on the blog.

Rather than look at the obvious choice of Dragon’s Lair, I thought shining a light on a more obscure title would be more fruitful. I was fortunate enough to play an original Williams Star Rider last year at a fellow collector’s meet-up, and really enjoyed it (thanks Karl). The game itself saw a reasonably wide release over here in the UK, and I’m aware that a few cabinets still exist in a few arcades over in the US.

Laser Disc games don’t occupy a particularly memorable space in arcade gaming history. The genre had a very short shelf life, and at the time was seen as the saviour of the coin operated industry during a period of “me-too” stagnation, and an ever-increasing array of quality home conversions. In 1983/4, hopes were placed on this new technology to re-ignite the playing public’s enthusiasm for arcades.

Indeed, 1983’s Dragon’s Lair released by Cinematronics combined the now legendary art of Don Bluth with some innovative interactivity. Players felt like they were playing a cartoon, and although in reality the game was about pressing buttons and moving a joystick at the right time, the game was a much need shot in the arm to an ailing industry. Other companies followed suit, releasing similarly structured laser disc titles, or using the graphical wow that streaming footage from a laser disc could provide, as a backdrop to traditional video game fare – Firefox, MACH 3 and Astron Belt are good examples here.

Williams though decided to sit on the sidelines early on. With a great pedigree under its belt already (Defender, Stargate, Joust and Robotron to name a few), it wasn’t impressed with the early forays into the digital disc world in late ’82 early ’83. Ron Crouse, Director of marketing at Williams, explained at the time of Star Rider’s release:

We were not happy with what the discs could do then. There were a few early prototypes, but they were being produced with mainly poor results. We wanted to do a genuinely interactive game, but the capabilities at the time were so limiting…….We needed to be able to change the player’s perspective when he or she plays the game.

And this was understandable. What Williams quickly identified, was that the levels of player interaction with Laser games up to that point was very limited. It was a case of style over substance, and they sought to change that. Additionally, the technology used was fraught with problems. Laser games already had a reputation for unreliability.

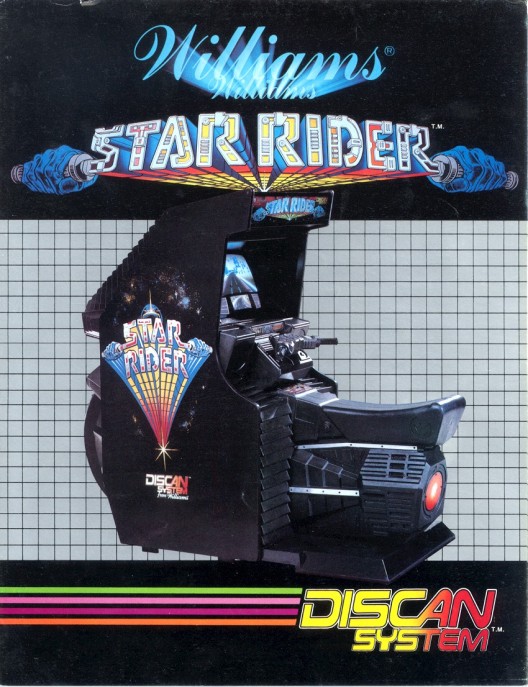

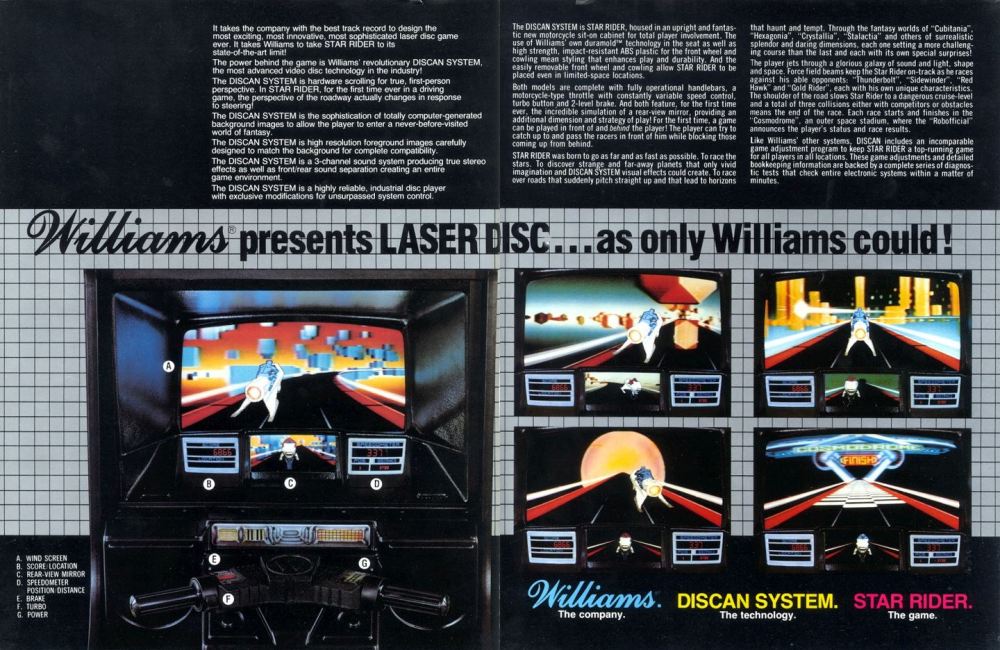

And so in February 1983, the engineers at Williams started working on hardware that became known as the Discan System. This was coupled with a first person driving game idea, and ultimately led to what Star Rider would become. The Discan System in essence gave the player an opportunity to shift their field of view while playing the game by basically zooming in and out of areas on-screen, depending on the direction of movement using the handlebar controller. What’s more, the speed at which the disc is read and displayed on-screen, is determined by the player also, through the use of the brake, throttle and turbo inputs.

So what you end up with is a game where rather than being pushed along a pre-determined path where every game is identical (as in Dragon’s Lair for example), the player gets visual feedback based on what they are doing with the controls – and so arguably, every game is different. Think Pole Position but with amazing graphics.

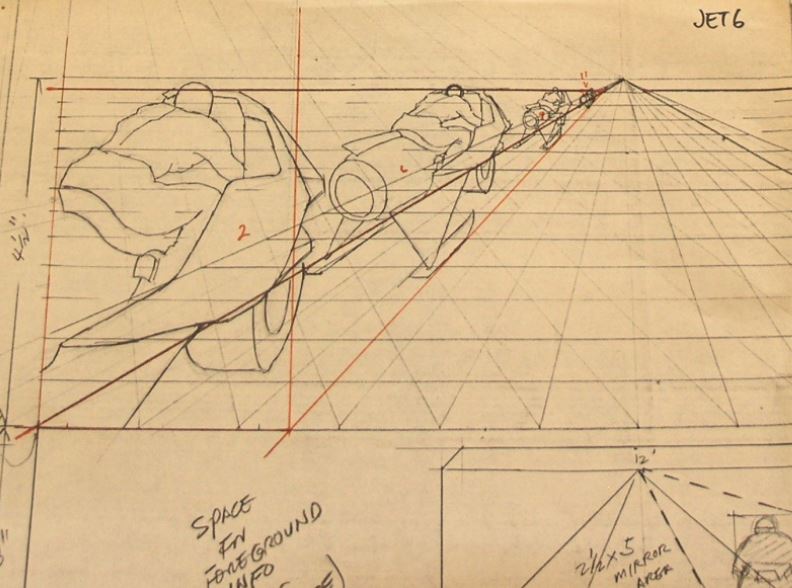

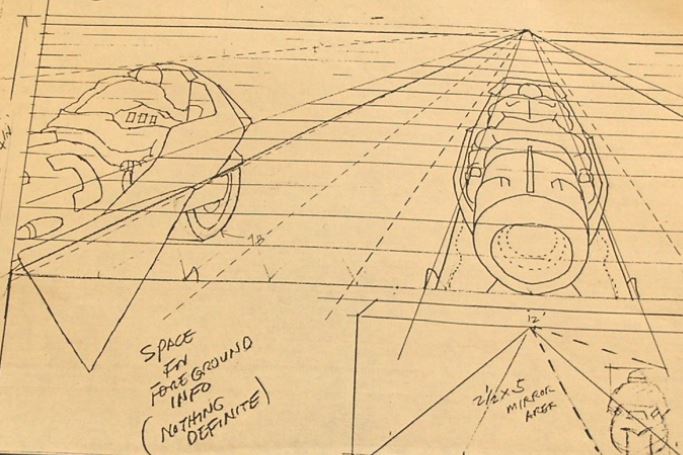

And it is the visuals that set Star Rider apart from any other driving game of the time. Williams brought in the services of the now-late artist Python Anghelo who designed several courses based on different futuristic themes. This was some of his original hand-painted artwork for Star Rider:

Anghelo’s themes here were further developed in-house and given the names Cubitania, Hexagonia, Crystallia, Milky Way, Titania, Stalactia and Metropolia. These initial concepts were used to create the look and layout of the courses.

John Newcomer, the game’s manager of design, spoke with me about Anghelo’s influence on the game:

I worked with Python more as a manager/intermediator to help him get his ideas implemented throughout engineering. Can validate that this game was Python’s brainchild. The concept, the motorcycle idea, the worlds. He guided Jack Haegar on what the pixel art should look like for the bikes and Robofficial. I watched Python storyboard the worlds and tracks and interface with art manager, Bes Nievera. Python created within the limitation that the computer graphics had to be simple so he invented worlds that were very geometric.

Python will always be a creative inspiration to me.

Williams engaged a third-party company, Computer Creations – who up to that point were well-known for their special effects work in television commercials – to develop the final footage, using state of the art computers. This video shows some of the raw footage built and used in the final game:

(Huge thanks to YouTuber “Retro Bach” for archiving this video)

Although primitive by today’s standards, this was truly cutting edge for 1983 – matching the visuals of the movie Tron easily. I would imagine it was pretty mind-blowing for any teenager to see outside of the cinema screens of the day.

But what about the gameplay? Williams was keen to break the mould of Laser Disc games to date, and worked hard to create a game that would fit the incredible background footage produced by Computer Creations. Crouse explained what the company were aiming for:

I feel you have three priorities in designing a game of this type. First is sight. it has to be visually exciting. Next is sound. The game’s audio effects have to sound realistic. Finally is the gameplay itself. It has to really grab you the first time you stick a quarter into it. We didn’t want to the game to look like a bunch of computer images that looked like a bunch of computer images projected over a filmed background.

It was all hands on deck – nearly all the company’s engineers, programmers and artists worked on the game at some point – some worked seven days a week to battle with the new technology.

The player’s opponents were created to act as randomly as possible to remove the element of repetition (again further distancing the game from the genre as it was up to that point). Each had its own behaviour attributes – much like the ghosts found in Pac-Man – some race more aggressively than others. Visually, the graphical style used merged the streamed footage and sprites surprisingly well.

There were a few innovations too, like the addition of a rear view mirror, located at the foot of the screen, which gave players an opportunity to block opponents as they charged from behind. Here’s some footage of the game in action:

So what you end up with is a futuristic racer that drops the player into a fantasy world with a certain level of interaction. Racing other bikes through bizarre colourful worlds was certainly a unique proposition. Adding to the overall package was a cabinet design like no other. As a full upright cabinet, Williams added plastic moldings (at great expense) creating a front wheel and seat design, and three speakers that blast sounds at the player. What was ultimately released looked like a crash between a motorbike and an upright arcade cabinet – but in a good way!

John Newcomer also spoke of the challenges of the game, and the gamble that Williams was taking on Star Rider:

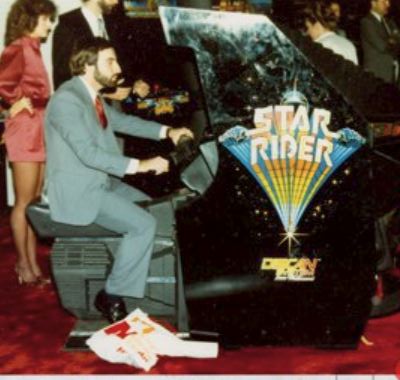

Literally, everyone in engineering was working round the clock to get this game done in time for the AMOA industry show of that year. The gamble was that distributors were only interested in buying laser disc games because they hoped “the next big thing” would save the arcades. They saw the huge success of Dragon’s Lair and Mach III also did well. We were simply late to the party and took on too many new innovations for Williams in all departments. Laser disc was new for us and engineering had to tackle the reliability issue. The plastic cabinet was new. The hardware was new with an expander board that stretched the video so you could steer off the road. Working with Computer Creations and 3D rendering was new. The motorcycle handlebars were new and the reliability of them was a problem for us.

Here are some pictures of Star Rider being displayed at the Williams booth at the AMOA show that John references above:

Even 30 years later, the game is a visual treat to look at and play.

It was clear that Williams was betting big on this game. Development costs came in at just under $4 million. This was a staggering amount, some four times the cost of creating any previous game at the company. They couldn’t really afford to take a bath with Star Rider and the company had a target to sell 10,000 units at over $3,000 apiece. Having just announced a $5 million dollar pre-tax loss for the fourth quarter of 1983, this game had the potential to either rescue or further damage the ailing company.

As it turned out, Star Rider was not a commercial success. Add to the development bill the cost of design, production and distribution, and the eventual impact on the fortunes of Williams was huge. Eugene Jarvis describes Star Rider as a “major dog” and cites total losses of around $50 million.

Newcomer recalls the chaos building up to the AMOA show, where Star Rider was showcased:

Literally the math [underneath he hood of the game] had to work out to completion by AMOA so number of vertices per frame was everything. I think in the end we added the last two worlds after the show. Cabinets were shipped to the show without ROMs. I literally carried the ROMs on the plane the day before the show after 3 all-nighters and I stuck my hand in the door as the gate door was closing [at the airport]. We were that close to not having ROMs when the show opened. It hurt so bad that the game was a flop, a very bitter pill for everyone to swallow. Everyone worked so hard and there was so much talent on it.

A variety of factors were at play here – the initial cost of the machine, the marketplace at the time and the technology used – operators complained of quickly failing laser disc units in all laser games. Whilst Williams resolved some reliability issues by creating their own-specced player, they suffered from a demoralised market for this type of game.

I’d also add that the cabinet shipped as an awkward shape. The front wheel would have required some creative placing in an arcade alongside other arcade cabinets with a more traditional footprint. That must have been pretty off-putting to operators. Here’s what a Williams spokesperson at the time had to say about Star Rider’s fortunes:

The year for lasers has certainly not been what we expected by any means. In the beginning, Star Rider was received very well. When it went into the arcade, yes, it was an attractive and popular game. it was right at the top of the charts. But as far as success was concerned, I guess it’s measured in many different ways. For a player there’s one measure of success. For us, it was not a success in the sense that we didn’t sell the amount we had anticipated.

Player apathy was certainly a factor. Quickly realising that many laser games were nothing more than pretty things to look at rather than to play, Star Rider was overlooked by much of the arcade gaming fraternity of the time. When players are giving games a wide berth, raw factory sales are going to dry up quickly. The manufacturers produced games based on demand after all.

Looking at it now, Star Rider was probably the most sophisticated of all the Laser Disc games, but didn’t really stand up to long-term repeated plays. It really is something more to be experienced, as it now represents an industry trying desperately to introduce new gameplay experiences to the general public just before the cliff-edge drop of the coin operated industry in 1984.

Newcomer’s thoughts are interesting:

[Star Rider’s] programmers were a who’s who of veterans who went on to do incredible things in the industry. The artists, mechanical engineers, hardware were all super talented and dedicated and put in their creativity. The managers rolled up their sleeves and worked with the team. Lesson learned. You can’t rush a game even with great talent and hard work. It has to be proved fun first, then expanded. You need to know that the timing will be right in the market when it is done. Sometimes you need to be involved in a flop to remind you to follow the basics and to evaluate honestly and raise your hand early to say something isn’t fun. I respect every single member of the Star Rider team to this day.

But do try to check out Star Rider – they are still out there (albeit in very limited numbers). It’s a quirky game that I think came out spectacularly well for its time.

Thanks for reading this week.

Tony

Great post. I remember seeing Star Rider at Southend-on-Sea when it first came out. You got quite a lot of play-time for your money, but the machine wasn’t there long before it had the out of order sign up. Didn’t make my jaw-drop, I suppose because I’d seen Astron Belt and Dragon’s Lair, which had already had that effect on me. It was certainly the best laser-disc game I’d played though back then. Dragon’s Lair always felt like 20p wasted, as it was just too hard I found.

That video clip of it the game being played looks like the disc was in a bad state. I don’t remember it being grainy and glitchy like that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dragon’s Lair at 20p a shot? Take my money! It was 50p a go where I frequented.

LikeLike

I’m probably talking rubbish. 30p – 50p sounds more like it actually. I do remember the feeling that I’d been ripped off from Dragon’s Lair, and also extremely jealous of the one kid I saw who was brilliant at it. How was that even possible, is what I recall thinking, before sloping off to play something that wouldn’t eat up all my money within a few minutes.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Have any been seen in the UK recently?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey George – there are two Star Rider cabs that I’m aware of here in the UK, both in collectors’ hands. One of them is certainly working, as I played it last year. I suspect there’s a few more too. I never saw one back in the day, but it seems there were a few out there on the arcade floors in ’83, ’84. More for the hardcore collector I would say, given the complexities involved in maintaining one.

LikeLike

This is great!! Star Rider was a big favorite of mine back in the day, and it’s always been kind of hard to find good information about it. I even have a Star Rider marquee in my collection, and I’m pretty sure it’s from the actual machine I used to play as a kid at the arcade. I would LOVE to play one again. Thanks so much for this article!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Superb article. The sit down version had speakers behind you so when passed by opponents you could hear them approach on the left or right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Admiring the time and energy you put into your blog and in depth information you provide.

It’s good to come across a blog every once in a while

that isn’t the same unwanted rehashed information. Excellent

read! I’ve saved your site and I’m including your RSS

feeds to my Google account.

LikeLiked by 1 person