The story of Centuri starts well before the Golden Age of arcade gaming. It was launched from the ashes of Allied Leisure formed by Ron Haliburton and Dave Braun in 1968. Allied released many well-known electromechanical and solid state pinball machines. It did actually dabble in the early video game craze – releasing a version of Pong in 1973. In fact, Paddle Battle supposedly outsold Pong itself. Spurred on by this success, a handful of further video titles were developed throughout the 70s resulting in a total suite of around a dozen (mostly unremarkable) titles.

After a decade of mostly uneventful performance, Allied Leisure was sold in 1979 to an investment firm, The Koffman Group. Allied was in bad shape and on paper was something of a dog. But Koffman had an impressive track record of turning failing corporations around. With the buzz of ‘video games’ ringing throughout business circles in the USA, Koffman saw an opportunity to rebrand the company with a view of entering the burgeoning video game market as a manufacturer that could compete at the highest level.

Engaging the services of a marketing agency to advise on the rebrand, Centuri was eventually chosen as the name to drive the business forward into the 21st Century.

Arcade video games were to be the company’s future.

New premises were found in Hialeah, FL and recruitment started. Two people worth mentioning here are Ed Miller and Bill Olliges. Both joined Centuri in 1980 from Taito of America, where they served as President and Vice president respectively. They brought with them extensive knowledge and contacts in the Japanese video game market. This would prove key to the way in which Centuri conducted business as an arcade video game manufacturer.

The first job was to make the old Allied Leisure plant more efficient. Pinball production was immediately halted, and a consultant was brought in to review the manufacturing processes already in place. Allied rather bizarrely had always insisted on designing and manufacturing its own components. Everything from cabinets, power supplies and coin doors right down to individual buttons and knobs were designed and fabricated in-house. This bespoke practice, whilst admirable, was rather expensive and required a great deal of resource to pull off. Not to mention, the warehouse was full of the over-produced parts – all sat doing nothing. Another thing quickly identified were the many staff admitting to having little to do during their working day.

A new ethos swept through the company – one of efficiency and cost-cutting. Staff were redeployed, retrained or pointed in the direction of the door (headcount was halved to just over 200). At the same time, Centuri went out to market to source cabinets, metal parts and components from third-party suppliers – all at a much reduced impact on the balance sheet.

As a new entrant into the video game market, Centuri were going up against the established companies already with a foothold who all had teams of designers and the necessary kit and resources to create their own in-house titles. Centuri had none of this, and building that sort of infrastructure would be nigh-on impossible, very expensive and of course would take some time – something they simply didn’t have.

So where would Centuri’s games come from? Ed and Bill quickly tapped up their contacts in Japan and pursued and acquired several licensed games for manufacture and distribution in the USA. This made a lot of sense for both sides. Japanese companies for the most part had no presence in the now huge USA video game market, and a USA based company like Centuri could acquire unique, new working video game PCBs at a fraction of the usual cost of developing them in-house. The games of course would never have been seen before on US shores. Joel Hochberg, a VP within the company explains:

Video development was in limited availability at Centuri, therefore, licensing of video games from Japan, if the company wanted to be in the video business, was essential. Many U.S. game companies embarked on a similar licensing program because Japan was developing so many video concepts.

This scenario was a win-win for both Licensee and Licensor. The Japanese companies now had a way to sell their product in the lucrative US market, and Centuri had a source of complete, fully developed games to sell and badge under their name. This strategy was to be the backbone of Centuri’s business model. Amongst he first batch of games acquired from overseas were Eagle and Phoenix. Both were massive hits. Phoenix especially sold in droves. This proved to the company’s management that the model was viable, and work acquiring new licenses was ramped up.

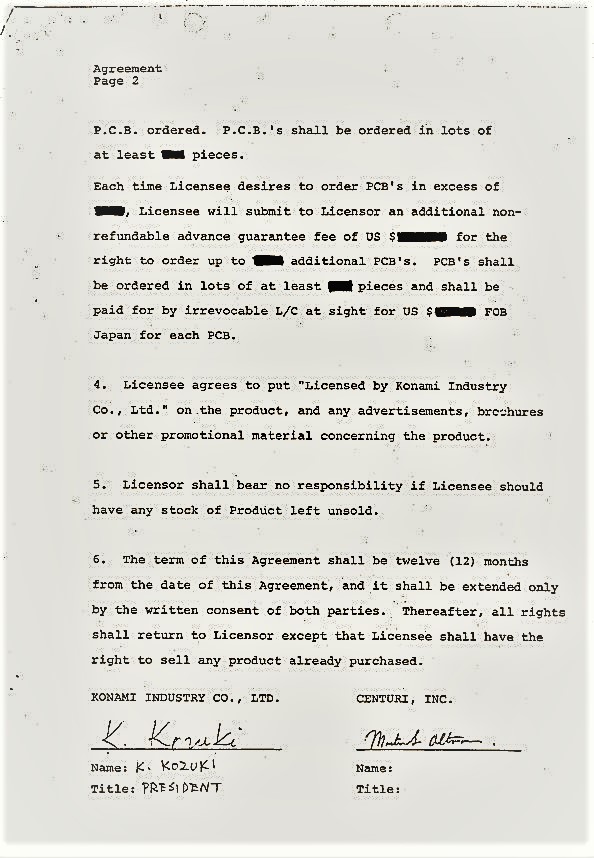

These relationships with Japanese development companies sat behind legal contracts. Time Pilot was one such game acquired under this arrangement, and here you can view the original contract between Centuri Inc, and Konami of Osaka, Japan:

Nice to see a simple two-page document covering the deal, rather than a huge ‘War & Peace’ style legal nightmare. This contract from Konami basically says “pay us some money, and we’ll send you the PCBs for the game”. Things were so much simpler then…

Time Pilot was a another big hit for Centuri and was released in the now familiar Centuri cabinet style. This cabinet was designed to house many of Centuri’s licensed games, with just a change of artwork and controls. Again, this all added up to reducing the company’s operating costs:

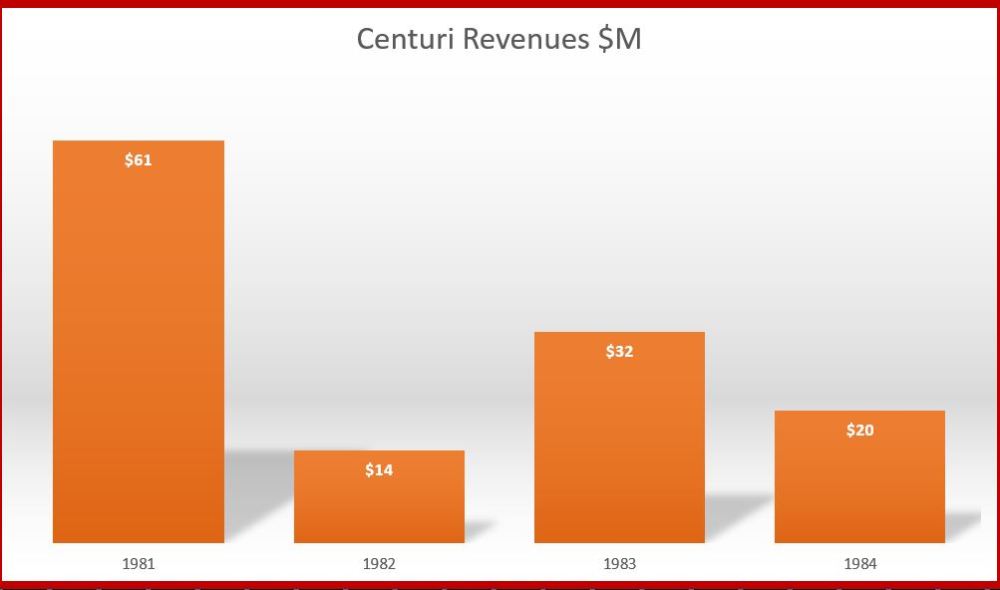

The huge majority of Century’s releases between 1980 and 1984 would turn out to be licensed games from Japan. Despite this new stability, the company’s video game revenues would still experience a roller-coaster ride during the Golden Age:

Centuri’s remarkable turnaround in 1981, placed them in the top five list of arcade game manufacturers behind Atari, Williams, Midway and Stern. Not bad for a company that was literally months old at the time. Maintaining these levels however proved to be a major challenge.

Centuri would eventually source, build and release many licensed games from the likes of SNK, Nichibutsu and Konami. Many of these games are now regarded as cornerstones of the classic era of arcade gaming. Games like Eagle, Phoenix, Gyruss, Track & Field and Vanguard.

After a lean 1982, Gyruss and Track & Field accounted for 70% of Centuri’s video game sales during the following year. Track & Field would spawn a sequel in Hypersports in 1984, and the Centuri licence sold well. But their relationship with Konami would soon come to an end.

But it wasn’t all licences for Centuri. I’ve already written extensively about the incredible Aztarac game on the blog here and here. Aztarac would be one of just a handful of games written and developed in-house by Centuri. Recently, I was fortunate enough to talk with Lee Feuling, who joined Centuri as a junior programmer in 1981. He shared with me some interesting snippets about his time with the company:

Back then I had worked at a couple of programming companies in Miami doing standard accounting software packages. While I generally enjoyed that type of job, I always thought doing graphics and movement software, as was being developed in the video game industry, would be great. So I decided to walk in to Centuri one day to explore the possibility of my employment.

The first person I met when I walked in was Tim Stryker. He was playing Aztarac in the entrance hall of the R&D department. When he saw me, he quickly swung around, spreading his arms to block the game, as though I was a competitor’s spy. We talked for a while, and then Tim took me to meet the other Centuri programmer, Hal Dean. As best I can remember, I was hired after an intro discussion with Hal. This was a much simpler time regarding the complexity of the employment process and besides, I came cheap!

Lee was hired, and worked as an assistant to Tim and Hal; designing and animating sprites and creating sound effects for various in-house games.

Steve Zarzecki was the lead hardware designer and he was assisted by Willie Maybohm. There were a couple other characters who passed thru there, but I’d say we five alone, constituted the in-house Centuri game development team.

I asked Lee about any “them vs us” vibes going on within the company. How could this tiny in-house team compete against the main Centuri strategy of acquiring licences from Japanese developers?

I seldom dealt directly with anyone outside the R&D department, especially in the early days. I’m guessing now, but I don’t think anybody in our department had to “sell” our abilities to management. I would have said that they (management) would have preferred developing in-house games over licensing agreements. This idea was based on an unsubstantiated belief that we were cheaper overall, and that companies, like Konami, who gained fame through Centuri license deals, would eventually grow into stand-alone competitors. But I gave it little thought.

After honing his programming skills as an apprentice, Lee was set loose on his own. He actually developed a game titled Freddy Flames. In the game, players assumed the role of a fireman named Freddy who was charged with killing all the fires in a burning home. The fires would grow and then divide and run around the three-story home threatening mainly Freddy in a kind of Donkey Kong way. The player’s weapon was a simple fire extinguisher on Freddie’s back.

It fired nearly across the span of the house when it was full. But, as it emptied, the pressure and so the distance it fired, decreased. You could refill your extinguisher’s water supply at one of several broken and leaking pipes in the house.

Lee’s game tested, as did all others, by being placed in a couple of the local arcades to gauge player enthusiasm. Although Freddy did not raise the needed level of interest, Aztarac did. The game sounds very interesting (to me anyway!) – what a shame it didn’t see a full Centuri release.

Lee parted ways with Centuri soon after writing his game and followed Tim Stryker (who he now regarded as something of a mentor) to his new venture, Galacticomm. Centuri themselves soon after decided to close their video game division to focus on other areas of the business (like boat repairs would you believe). At the end of 1984, after dabbling with the idea of selling cabinets directly to operators (rather than via distributors), and upsetting its customers, faced with licenses that were drying up and tough market conditions, the assets of the video game business were sold off to the highest bidder, and Centuri Inc was no more.

Centuri cabinets today are fairly common in the USA, and make for nice-looking collectable pieces:

Centuri’s legacy should not be underestimated. Although an entity in the arcade video game market for just four years, some of the greatest games of the early 80s came from their production lines. These are games that still stand up today.

So that’s your lot for this week – hope you enjoyed this summary of the short lifespan of Centuri; definitely a small but distinct minnow in a huge pond.

See you next week.

Tony

Many thanks to Lee Feuling for agreeing to talk with me about his time at Centuri back in the day. Also to John Anderson for sharing some great info. Further reading on Centuri can be found at Centuri.net

In memory of Bill Olliges, who passed away in March 2018 aged 81.

Joel Hochberg then went on to form Rare with the Stamper brothers of Ultimate, I’d be interest in the story of how they met, I suspect Centuri may have tried to license some of their pre-Ultimate arcade games, when they were still ACG (Dingo, Blueprint) – but I can only speculate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So much I did not know! Glad you were able to connect with Lee to pick his brain and see things from his very youthful perspective. I have stayed in touch with Lee and his wife Holly over the years. They have been good friends to the Stryker family.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome write-up. Phoenix is still one of my all time arcade faves. Track & Field was really amazing too. I liked the game, even though I was never a sports fan. Was Centuri one of the first to make standardized cabinets or were there already others?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good question. Most early manufacturers of cocktail games used a common design (Universal, Taito, Nintendo, Atari). For uprights, Atari were toying with the idea around that time – some of their cabaret games share identical shells, and of course a few years later the System 1 & 2 cabinets were designed to be ubiquitous through many games (Marble Madness, Indiana Jones etc) with a change of control panel and marquee. Nintendo used their standard upright cabinet design for Donkey Kong and many other games (Popeye, DKJnr etc). But it was the appearance of the Jamma standard a few years later that really popularised the concept. It’s weird given the focus on profits, that more manufacturers didn’t take the same approach as Centuri and use a common cabinet for all their games.

LikeLike

Centuri also sourced the cabinet graphics from Willis and would become one of their (Willis’) largest customers in the 80’s. Not all Willis artwork is bad!

LikeLiked by 1 person