My annual trip to the USA this November was in two parts. Aside from dropping into Free Play Florida, I’d decided that en-route, a whistle-stop visit to the American Classic Arcade Museum was in order. Joining me on that leg of the trip was my mate and fellow Brit arcade collector Richard May. So this week, rather than me bang on for the umpteenth time about ACAM, I thought it would be a great idea to hand the controls over, and have him share his perspective of this mecca of Classic Arcade Gaming as a first-time visitor. Over to Rich!

As my partner in video arcade collecting crime punts our rental Nissan around the leafy perimeter of Lake Winnipesaukee, I imagine arriving at a closed Funspot; shuttered for winter and guarded by a seven-foot-tall mascot that’s just asking to be punched on the nose.

Fortunately for Topsnuf the Dragon, my surrogate Clark Griswold is Atari Missile Command grandmaster Tony Temple. He’s not a man known to crack under pressure. And they only switch the lights off here on Christmas Day.

Tony is a dab hand at the slow reveal. Like a seasoned tour guide, he deftly chaperones me away from the The American Classic Arcade Museum side entrance and we cross Funspot’s main threshold proper.

I shake hands with octogenarian founder, general manager and local figurehead Bob Lawton. He’s chairing his morning staff powwow in the Formica-clad interior of the Braggin’ Dragon cafeteria. The walls here are a shrine to Funspot’s storied past. While it is no longer the ‘Largest Arcade in the World’ (Doc Mack’s Galloping Ghost in Illinois now has the edge in terms of sheer numbers) it can be wholly forgiven for clinging to the accolade. Certainly, few others have its provenance and chops.

I’m already distracted by the Daytona USA Championship setup nearby. It’s not really my thing, but without doubt a modern video arcade success story if there ever was one; triumphantly holding the fort as the redemption machine army hammers away at the gate. And you don’t see ten in a row every day.

Aside from said NASCAR themed behemoth, a lovingly restored electromechanical Shoot The Bear (Seeburg, 1949, American Restoration star) and a delightful little Leprechaun cabinet (Moppet Video, 1982) there is very little to hold our attention down here, so we make our way up to ACAM.

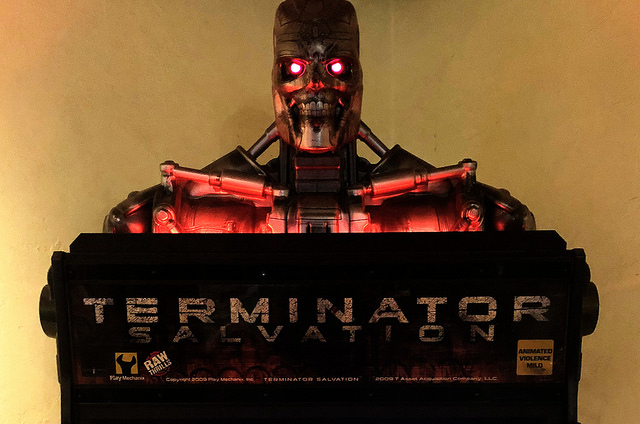

Passing through the second floor I note Funhouse (Williams, 1990), Kiss (Bally, 1979, apparently Bob Lawton’s favourite) and Superman (Atari, 1978) pinballs, a Simpsons (Konami, 1991) and a Terminator franchise miscellany. The mean and menacing topper for Terminator Salvation (Raw Thrills, 2010) is a thing of beauty; far more than can be said about the game itself.

As we climb to the third floor, I notice it; that familiar olfactory comfort blanket for vintage video arcade nerds the world over. The distinctive odour, like damp cement with a top note of charred newspaper, of dusty cathode ray tubes at peak temperature. Clark, I really don’t want to go home.

This is ACAM president and curator Gary Vincent’s “Immersive environment”. And it’s truly captivating. Around two hundred arcade games (with over a hundred more in storage, rotated in from time to time) dating from the early Seventies to the late Eighties, grouped by developer and/or publisher. The entire space is enveloped in evocative red light, punctured by staccato rows of incandescent marquees and the phosphor glow of CRT screens.

I wander around in a daze, not knowing what to focus on, let alone actually pop a token into. Where else can I play the following all under one roof: Exidy’s 1976 classic Death Race (instigator of the United States’ very first video game moral panic, years before the likes of Carmageddon and Grand Theft Auto); Nutting Associates’ Computer Space (the first commercially available video arcade game in 1971, here resplendent in metalflake red); Sega’s sprite-scaling masterpieces Outrun (1986), Afterburner (1987) and Space Harrier (1985); all-time platformer classics like Zoo Keeper (Taito, 1982), Burgertime (Data East, 1982) and Mario Bros (Nintendo, 1983); the common yet no less compelling Pac-Man (Namco, 1980), Centipede (Atari, 1981), Space Invaders (Taito, 1978), Donkey Kong (Nintendo, 1981) and Galaga (Namco, 1981).

The entire Atari X-Y back catalogue (including the wonderful, rare Quantum, 1982); oddballs like Nichibutsu’s Crazy Climber (1980, ACAM’s being Taito’s release); every Universal release (stunning cabinets with glorious art but woeful, derivative games on the whole, perhaps with the exception of Cosmic Guerilla, 1979); black and white dinosaurs like Fire Truck (Atari, 1978) and Bandido (Exidy, 1979) and… I could go on, but you get the idea.

I’m no stranger to a contemporary arcade filled with older machines, like Andy Palmer’s ever-expanding Arcade Club in Greater Manchester here in the UK, and the small but perfectly proportioned Arcade Odyssey in Southwest Miami. But ACAM’s raison d’être is unique: a 501(c)3 nonprofit established for ‘the purpose of collecting classic games through donation to preserve the history of classic coin-op games’.

Whatever game springs to mind when one Wayne’s World dissolves back to Nineteen Seventy or Eighty whatever, chances are it’s on the floor here. But the real gems are the ones that weren’t so ubiquitous, even in the arcade boom years.

Writing as a Brit raised in the East Midlands of the UK, pickings were always slim. I never saw the aforementioned Quantum or a Star Trek Captain’s Chair (Sega, 1982), let alone a Tunnel Hunt. The latter – originally with the working title of Tube Chase – started development by Owen Rubin (of Major Havoc fame) at Atari in the closing months of the Seventies, and was his first vector project.

Rubin was inspired by the USCSS Nostromo’s planetfall scene in Ridley Scott’s Alien. However, after several months of development he couldn’t get it working as a vector game. It quickly became a raster endeavour. An ellipse generator was employed for the winding, high-speed first-person tunnel rush sections and the game featured brief moments of respite into open space before allowing the player to choose a branching tunnel (in much the same way that games like Outrun would do some years later).

Customer feedback during location testing, though largely positive, never quite satisfied Atari’s stringent requirements, so the game was withdrawn for further streamlining, essentially to make it cheaper. A rectangle generator was swapped in for the tunnels, the branching options were removed and the game placed back on site.

But it still wasn’t cutting the mustard for Atari. The company withdrew it and made the then unprecedented decision to sell the game to a competitor, Exidy. Rubin continued to work on the game, now titled Vertigo. He spent a long time removing his own anti-cloning security code because he actually couldn’t remember where it was. It was field tested yet again, this time in a cockpit cabinet, only to receive even less impressive customer feedback.

Exidy decided to cut its losses, selling the game to Centuri where it finally found a home as Tunnel Hunt with an ‘Licensed by Atari’ credit on the marquee. Somewhat dated upon release due to its long gestation period, the game is, in 2018, a mind-bending, borderline psychedelic thrill.

One leans slightly forward, the huge plastic monitor cowl eliminating all other distractions. It’s exactly why playing this in a real, noisy arcade is the definitive Tunnel Hunt experience. You embark on an increasingly rapid, disorienting journey through a series of colourful, blocky tunnels.

A targeting cross hair is employed for the swift elimination of enemy ships. Pretty much like every other bad guy ship at the time, they had to be TIE Fighters. You must avoid hitting the tunnel walls, lest your limited shields become depleted. The exception to this being when doing so enables you to slow just a little in order to not overtake an enemy. I walk away from each attempt squinting, my head throbbing a little. It’s one of those games that, even if you’re fairly proficient, will eventually overload your frontal lobes due to its sheer intensity.

Retro Gamer magazine dubbed it ‘the spiritual precursor to Stun Runner‘ (released some years later in 1989) which is ostensibly fair but not quite on the mark. Despite the tunnel theme, it’s more the Death Star trench run (in the movie, not in the game of the movie) meets Bally Midway’s underrated Space Encounters (1980). On both amphetamines and hallucinogens. I love it, and I’ll probably never see another one.

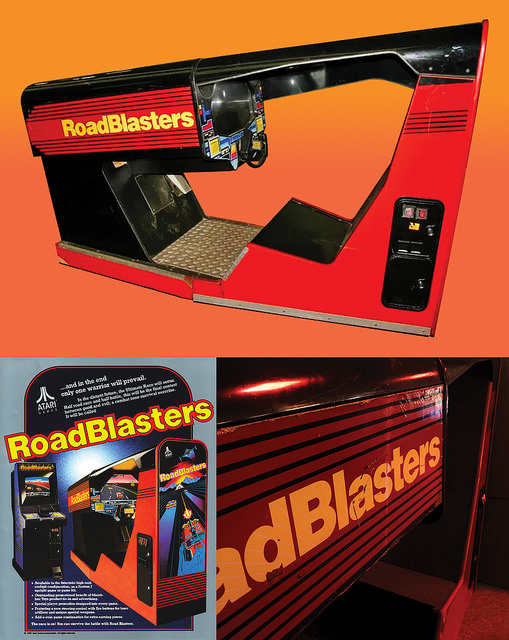

I put some time in on Looping (Venture Line, 1982), an addictive, hard-as-nails little oddity, before moving on to a rough but eminently beautiful Atari Road Blasters (1987) cockpit cabinet.

This is a mighty beast that presents itself as a long, low-slung, futuristic sports car (as imagined in the late Eighties) sans wheels. It’s something I’d never seen until now, uprights being the norm in the UK. I recently read a blog post detailing one collector’s butchering of an admittedly water-damaged Road Blasters cockpit, chopping it back to install a racing seat from a modern game. Not a pretty sight. Please don’t do that at home.

The late Kan Yabumoto’s sublime Mad Planets (Gottlieb, 1983) is a game neither Tony or I can resist returning to. No matter what else we play and pontificate about, Mad Planets has us by the short and curlies. We hover over each other, chomping at the bit to get the higher score. It’s a hard-to-find, finely honed and innovative shooter with only 1400 cabinets ever manufactured. In my alternate timeline 1983 it’s every bit the quarter-muncher as Robotron or Defender. Read more about this brilliant game here.

The monitors of Atari’s vector lineup could do with some tweaking, and Rubin’s Major Havoc was sadly unplayable due to some sticky controls. But Star Wars has lost none of its charm and Bruce Merritt’s Black Widow is as brilliant as ever. Elsewhere, Tony and I pop a fair few tokens into Death Race, one of the most eye-catching cabinets here and something we’re very unlikely to encounter again in the wild until we return. Then we take a quick break to check out Funspot’s charming Mini Golf course, the majority of which was once located outside the venue from 1964 to 2014. We don’t play a round; there doesn’t seem to be enough time to do that and play video games, irrespective of our tired eyes.

A cursory eyeball of Atari’s 1979 giant novelty pin Hercules and then Tony introduces me to Gary Vincent, the man behind the magic. Gary is the consummate host, taking time away from what is clearly a very busy schedule to show us around his lively workshop and small monitor storage facility.

He walks us through his latest display, a line of unique, giant metal and plastic Sente Technologies cabinets accompanied by a display full of related ephemera, technical documentation and a detailed history. Founded by ex-Atari employees, Sente was eventually bought by original Atari cofounder Nolan Bushnell and incorporated into his then fledgling Pizza Time Theatre Company (soon to be known as Chuck E. Cheese).

The company went on to develop the Sente Arcade Computer system but was almost halted in its tracks by an Atari lawsuit. When departing Atari in 1978, Bushnell was forced to sign a non-competitive agreement lasting several years. This basically meant no video games. Perennially light on his feet, he averted disaster by signing a deal with Atari granting them exclusive rights to home versions of Sente releases.

The SAC allowed operators to swap out game PCBs, control panels and marquees whilst retaining the main games cabinet. Going live a year before the popular JAMMA standard was introduced (and a fair few more before it became omnipresent) the SAC was well ahead of its time.

We then chat with Gary about the difficulty of keeping ageing CRT monitors alive for an operation of this scale. Initially surprised that a non-profit – forever grateful for donations – would struggle so profoundly in this department, we are reminded that Funspot is open 364 days of the year. Nothing is ever switched off, unless it’s sleeping or broken. It’s a sobering memo-to-self that this old tech will, at some point, regardless of the care and attention lavished upon it, eventually die.

Here’s a great little kitchen-sink documentary about Funspot and, of course, you can read Tony’s original post about the history of this place here.

The art… is inseparable from its canvas, which during the 8-and 16-bit eras was the CRT television or monitor. Pixel art… was made on and for the phosphors of those displays, and exploited them to achieve a smoothness and verisimilitude impossible with mere pixels.

– Duncan Harris, author of The Bitmap Brothers: Universe

I console myself with the certainty that I’ll be returning for many more years before this glorious, painstakingly curated collection of arcade awesomeness is put out to pasture.

Richard May is an occasional graphic artist and full-time video arcade game enthusiast. Find him at richiemay.com or on Instagram.

Excellent article! Am I reading correctly and that man in the photo is in his 80’s? Does not compute…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love this story. I’ll get to FunSpot one day!

LikeLike

Awesome! I wanna go there too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just played that Terminator Salvation game yesterday at the Arcade inside the skating rink where I took my son. Spent the rest of my time playing Ms. Pacman and got the highest score that I have ever gotten. I was pretty impressed with myself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Funspot has been my favorite arcade since the early 1990s. We use to spend part of every Summer at Weirs Beach, right down the road. It’s amazing to see how much it’s grown in size, and popularity. I could spend all day in the classic arcade room.

LikeLiked by 1 person