Much has been written about Pac-Man. This was a huge game for Namco back in the early eighties that would grow into a true 20th century icon. Everybody has at least heard of the game, because it was one of the first to enter the realms of popular culture. Indeed, merchandise and endorsements earned Namco more in revenues than actual hardware sales of the game.

Across the globe, instead of ordering a single unit of the new games as was usual, operators placed orders for multiple cabinets, such was the demand. This was seen as a sensible strategy in the face of losing potential income from customers having to queue to get a game. They just placed more machines on the floor to get more coins into the cash boxes quicker – this was good news for them and good news for Namco.

Pac-Man’s creator, Toru Iwatani joined Namco in 1977 aged 22, when it was still known as Nakamura Manufacturing. His first role within the business was to repair failed game boards from licensed black and white Atari video games that were distributed throughout Japan. Repairing hardware wasn’t where Toru wanted to be at the time – he was a big fan of pinball, and suggested to his bosses that he worked on a video version of pinball. And so it came to pass that Namco had some early success with it’s first arcade video game, Gee Bee, developed by Iwatani. Buoyed by it’s success, Namco followed this up by 1979’s Galaxian, the first ever video game to use colour RGB graphics, something of a revolution at the time. Galaxian was a huge hit, taking the basic concept of Space Invaders, but adding kamikaze enemies into the mix, that dive-bombed the player.

Iwatani-san was seeing the market domination of these “me-too” early shoot-em-ups of the time, and took inspiration from Atari across the pond, who were receiving massive adulation (and income) for its games, which were bright, colourful, and followed many different themes and concepts. He was inspired by the “happy” nature of the games he saw coming from Atari, and sought to imitate this model.

Rather than focus on shooting things, Iwatani explored themes that might appeal to families and females, who up to this point, hadn’t embraced video games in the same way that men of the world had:

In the late Seventies, videogame arcades, which in Japan we call ‘game centres’, were just playgrounds for boys and young men. The only videogames on offer were brutal affairs involving the killing of aliens. My aim was to come up with a game that had an endearing charm, was easy to play, involved lots of light-hearted fun, and that women and couples could enjoy. When it came time to figure out what sort of game I could do, I suggested basing it around a particular verb. I thought up a variety of verbs, such as “grab” and “surround”. In those days, there was a proliferation of table top games, including a considerable number of game machines installed in cafés and other businesses. I figured that a game made in the image of a culinary environment and based around the verb “to eat” could be fun.

And so, together with a team of eight programmers and designers, Iwatani started work on his opus. The ideas came thick and fast, and were tweaked or dropped to suit the game over an 18 month development period.

The design for Pac himself came to Iwatani after ordering a pizza and removing a single slice. With a mouthful of hot pizza, he looked down and saw the character looking back at him. He made Pac-Man friendly, so that people could identify with him. Adding the ghosts, gave a “Tom & Jerry” scenario, that he thought would appeal to a wide audience. Despite suggestions of adding eyes, hair and other features to Pac-Man, he remained resolute, choosing to keep a clear, bold yellow character. As design concepts, both Pac-Man and the ghosts had a simplicity and endearing charm.

The initial concept for the fruit bonuses sprung from the notion that the drawings on slot machines found in casinos were American and cool.

Because Pac-Man was a game about eating, we started by adding cherries, strawberries, oranges, and other fruit. Once we began running out of ideas, we put in things like Galaxians and keys.

Warp tunnels were added late in the game’s development, and the power pills came about after an episode of Popeye resonated with the team, showing the hero of the cartoon eating a can of spinach and turning the tables on his nemesis Bluto.

One feature dropped were shutters, that opened and closed, blocking the path of the maze at certain points. This element created too much frustration during play testing and so was removed in the final code.

Iwatani wanted players to be drawn to his new game:

When you look at a game, you must be able to understand what to do immediately. You should be able to explain the objective in no more than two sentences. I don’t see that with modern games – they are very complex. Of course, these complex games attract hardcore gamers, but if you want wide success, you have to make something that is fun and simple. You can only do this by studying human behaviour. My first objective when creating a game, is fun. Fun has to come first above everything.

He also cites the player’s feelings when talking about Pac-Man. Being chased by ghosts within the maze, generates a feeling of fear and panic. This tension was a key driver for players, but he wanted to add a balance: the powerpills and the ghost AI.

“Dispersal points” were added, where ghosts can be seen literally turning on their heels within certain parameters, so that players wouldn’t feel constantly pressured, and were given time to breathe and think about their next move.

The ghost enemies, Blinky, Pinky, Clyde and Inky, took a huge amount of programming. Imagine four enemies constantly chasing Pacman using he same set of rules. Eventually they would turn into a line of beads, following our hero around the maze all using the same routine and rule set. Algorithms were made so that the four ghosts could pursue and still do their job, but with individual movements in four different areas, and so each had it’s own persona:

- Blinky, the red ghost chases Pacman directly

- Pinky, the pink ghost targets a position 32 pixels ahead of Pac-Man’s mouth

- The blue ghost Inky, chases at the mirror point exactly symmetrical to Pacman

- And Clyde, coloured Orange, has a random chase pattern

It’s worth noting here, that despite what the player might think, the ghosts do not have actual artificial intelligence; they simply follow an algorithm to give the impression that each has a mind of its own. So what you get is Pac-Man in the middle, and four enemies closing in on him, but each with their own personality – this created much more excitement and engagement for the player – generating a sense of fun.

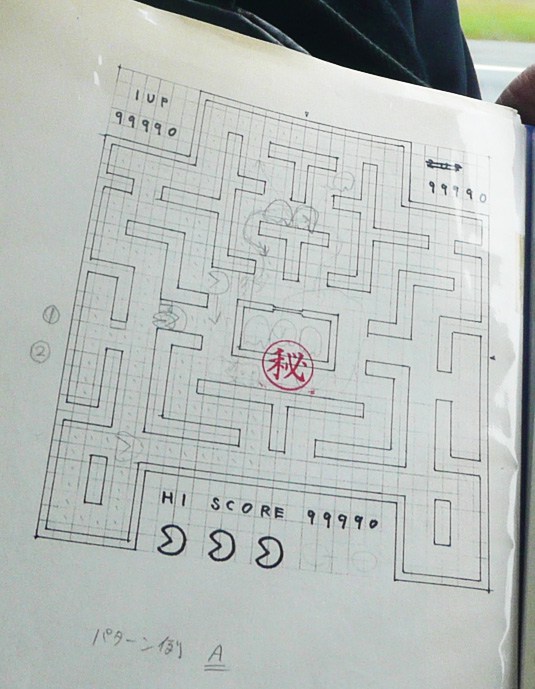

It’s interesting for us to have had sight of some of Iwatani’s original crude pencil designs of the maze and characters:

Described as “coffee breaks”, animated cut-scenes were introduced by Iwatani, another video gaming first. This was against the advice of one of his programmers Shigeo Funaki, but he saw them as an incentive for players to keep playing to see what would come up next, and insisted that they remain.

Again appealing to the human psyche, he wanted players to understand why their game ended, what they did wrong. He wanted players to to be able to create strategies to avoid ending their game in the same way. And of course, this meant players wanted to play again and again to advance the game.

With the basic structure in place, the game’s objective became more obvious, and the lead character soon gained his moniker, ‘Pakku Man’, based on Japanese slang ‘paku-paku’, which describes the sound of the mouth while eating. The original game’s title subsequently became Puck Man in Japan on it’s release. Going from “Puck” to “Fuck”, would be very easy in Western markets with nothing more than a pen marker and a quick bit of arcade vandalism, and so Namco executives in America hastily chose the name Pac-Man to avoid such shenanigans.

On its release in the USA in 1980, it is interesting to note that the game was initially overlooked by distributors and industry marketing executives. The feeling was that Namco’s Rally X game released at the same time was the machine to beat. However, by the end of 1982, over 400,000 Pac-Man arcade cabinets were sold globally, and an estimated 7 billion games played in arcades across America. The game was huge, it took everyone by surprise, and by the end of the decade had generated more revenue than the most successful film to date, Star Wars.

What’s interesting to note, is that despite this intimate relationship with his “baby” as Iwatani has often called him, Pac-Man continued to give up its secrets to players over the years. The first recorded “perfect” game, was achieved by Billy Mitchell of the USA, who recounts a story of meeting Iwatani after his achievement. Bill asked him about some things within the game that he had discovered, and wanted to know if they were intentional. After a hushed conversation with his colleagues, the answer came back:

Mr Mitchell-san, we don’t know. The game wasn’t supposed to be played that long.

So whilst Iwatani spent 18 months creating and “giving birth” to the game, it was up to the game itself to give up its secrets some years later for Mitchell and his fellow players to discover. There are a number of tricks and unintentional bugs within the game, like the ability to find a sit spot where the ghosts cannot see Pac-Man, the ability for Pac to pass straight through ghosts, and the infamous split screen at board 256 where the game ends due to the limitations of 8 bit code.

Some 35 years later, Pac-Man continues to be everywhere. It’s impact on the acceptance of video gaming as a valid pursuit cannot be underestimated. In addition to the many subsequent releases of the game since its iteration, the iconic shape still turns up all around the world.

For a more detailed technical read on Pacman’s inner workings, head over to The Pacman Dossier.

And if you want to learn how to complete a perfect game of Pac-Man, check out Jon Stoodley’s fantastic talk from a couple years back.

Thanks for reading this week!

Tony

Great article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

gran articulo, gracias

LikeLiked by 1 person